“David Lynch: The Art Life” Paints A Portrait Of A Beautifully Warped Mind

by Ashley Naftule on Apr 21, 2017 • 9:00 am 115 Comments

At one point in “David Lynch: The Art Life”, the snowy-haired artist shares a story about a time his father came to visit him. He took him downstairs, where he showed his father his “experiments”: a collection of rotting fruit and animal bodies. Lynch had been letting them slowly decompose in his basement so he could see the various new forms and shapes they took on as they broke down. As they ascend the stairs, an excited Lynch turned back around and saw that his father looked shaken. “David – don’t have children,” his father told him.

Directed by the team of Jon Nguyen, Rick Barnes, and Olivia Neergaard-Holm, “The Art Life” is a slow-moving, sumptuously shot portrait of one of the world’s greatest creative minds. We see Lynch puttering away in the amber glow of his Hollywood Hills studio, working on a series of paintings while his infant daughter stumbles around and sits by his side. With a stubby cigarette almost always gripped in his hands, Lynch has a calm, bemused air that makes him look younger than he is. The film focuses solely on him and his voice. Unlike most documentaries, there are no other narrators or talking heads entering the picture — his voice is the only one we hear.

The film covers his childhood, his training as a painter, and his life in Philadelphia up until he moved to L.A. and shot “Eraserhead.” If you come into the film hoping to hear anything about any movie he worked on post-“Eraserhead”, you will be disappointed. There’s nothing about “Twin Peaks” or “Mulholland Drive”; Lynch doesn’t explain what the fuck “Inland Empire” was about or if Robert Blake was as creepy off-camera as he was on-camera during “Lost Highway.”

While it’s initially disappointing that we don’t get to hear the man talk about some of his greatest works, it helps to preserve the mystery of those films. Even when “Eraserhead” gets discussed, he keeps his process and philosophies close to the vest (decades later and he still won’t explain HOW he made the baby from “Eraserhead”). But what he does talk about is fascinating, and sheds some interesting new light on his body of work.

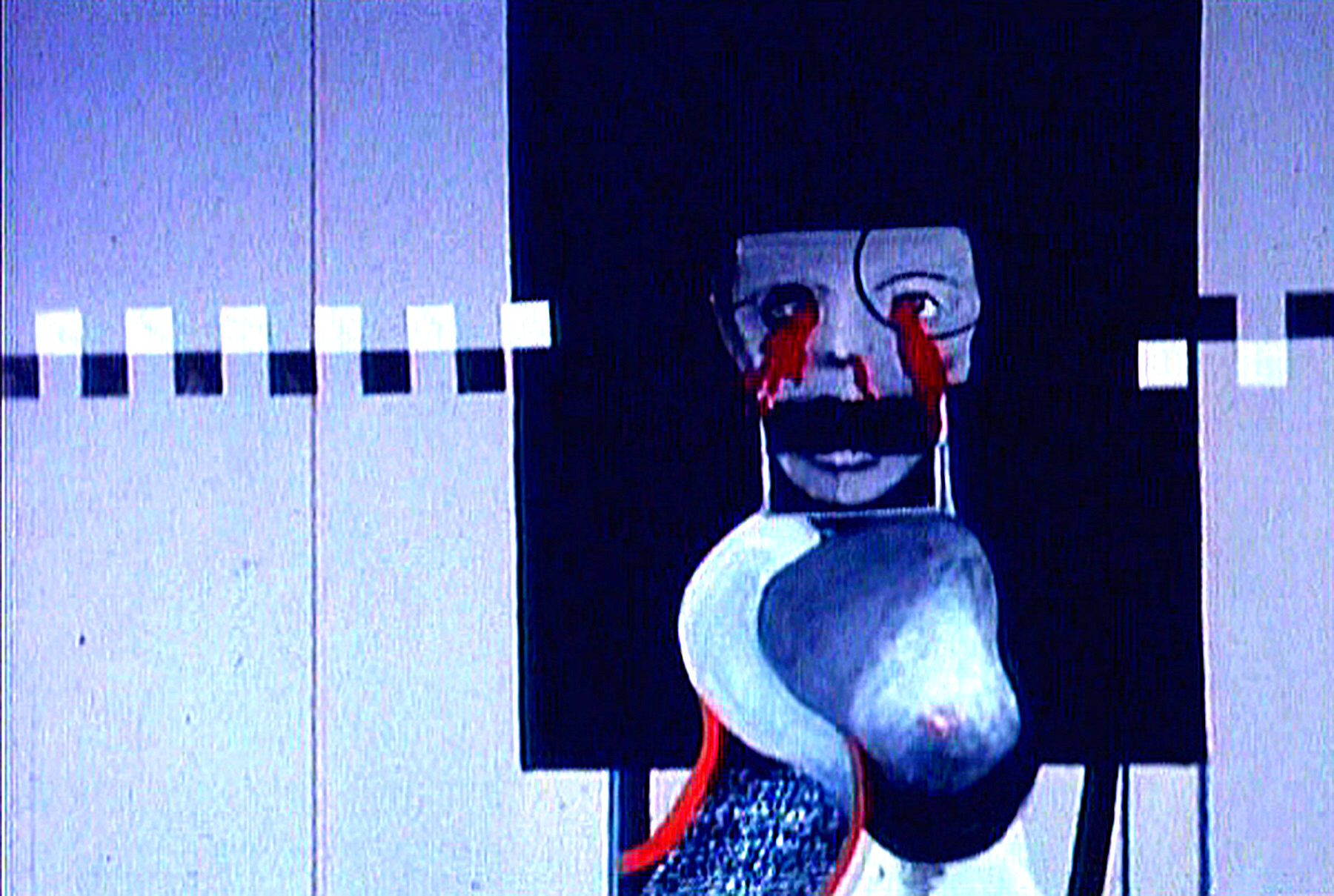

The Alphabet

We hear him talk about his loving and conservative upbringing, as well as the occasional bursts of weirdness that warped his brain (like seeing a naked woman with a bloody mouth cross the street in broad daylight while he and his brother were playing outside). He hilariously undercuts his image about being an overgrown boy scout by sharing some amazing weed stories about getting high with his roommate Peter Wolf (from the J. Geils Band) and stopping his car in the middle of the freeway because he was hypnotized by the white lines. And he reveals his deep passion for painting, something that he’s been obsessively working on since his teenage years.

The most resonant parts of the film (and the one that will probably strike a chord with anyone trying to live a creative life) is how well it captures the struggle of getting by as an artist. It paints a picture of Lynch as a broke artist with a wife and a child, working a printing job that he hates, trying to get by in the slums of a city he hates. Lynch comes across as a man who lives to create, and anything that gets in the way of that is an irritant at best, and soul-destroying at worst.

It’s that struggle that really humanizes the impish filmmaker. You can hear in his voice, reflecting on those years, just how much that took out of him. And in the film’s most emotional moment, when he talks about the profound gratitude and relief he felt when he won an AFI film grant for his short “The Alphabet”, he’s at his most vulnerable.

When he talks about the freedom and possibilities that grant opened up for him, and how it gave him a way out of his life in Philadelphia, you can see the gears turning in his head: Lynch envisioning an alternate personal history where he didn’t win the grant, never left Philadelphia, never made “Eraserhead” or any features, and lived out his days as a painter struggling to make art when he wasn’t winning bread for his family. It’s an intense moment of “There But For The Grace of God Go I” that plays across his face and seeps into his voice.

It’s also perhaps the best argument for the continued existence of federally funded art grants I’ve seen on film. Imagine how different our world would be if Lynch DIDN’T get that grant. No “Eraserhead”, no “Dune”, no “Elephant Man”, no “Blue Velvet”. Nobody at bars screaming “FUCK THAT SHIT! PABST BLUE RIBBON!” No “Twin Peaks”, no Angelo Badalamenti scores — an entire generation of sinister dream-pop music snuffed out without the inspiration of “Questions In A World Of Blue” or “Laura Palmer’s Theme.” No cherry pie and coffee, Kyle MacLachlan, or backwards-talking dwarves. No “Lost Highway.” No Naomi Watts, cute as a button and tragic in “Mulholland Drive.” No horrifying clown face for Laura Dern in “Inland Empire”, no “Rabbits”, no Louis CK cameos. An entire universe of warped Americana that would have never sprung from his forehead was it not for that single American Film Institute grant.

Lynch doesn’t divulge too many personal details. We get a sense of the sacrifices and costs that came from his devotion to his work: a divorce, his own family begging him to give up on “Eraserhead” and get a job, falling out with friends. We also get a glimpse of Lynch as an intractable man when he tells a story about throwing Peter Wolf out after his roommate criticized him for walking out of a Bob Dylan concert.

“David Lynch: The Art Life” is a must-watch for fans of his work. I wouldn’t recommend it to casual fans or people looking for an introduction to his work: it’s too hermetic and tight-lipped for that. The film makes an excellent companion piece for Lynch’s short but sweet “Catching The Big Fish” book, which helps fill in some of the blanks “The Art Life” doesn’t cover.

If I have any major criticism of the documentary, it’s that it feels more like a DVD extra than a full-on film. As the supplement to any future Lynch release, it would be an A+ extra. As its own standalone release, it feels a little…. unfinished (the film has a very abrupt ending). I left the theater feeling like the film itself was like one of Lynch’s in-progress paintings: an obsessively labored over, intensely detailed frame of color and movement. I just couldn’t shake the feeling that there was more to the painting that I had just watched for 89 minutes.

Ashley Naftule is a writer, performer, and lifelong resident of Phoenix, AZ. He regularly performs at Space 55, The Firehouse Gallery, Lawn Gnome Books, and The Trunk Space He also does chalk art, collages, and massacres Billy Idol songs at karaoke. He won 3rd place at FilmBar’s Air Sex Championship in 2013. You can see more of his work at ashleynaftule.com

Donald P. Lovecraft, Or, The Doom That Came To Manhattan

No Volcano’s ‘Take My Chances’ Is Our Grossest Music Video Yet (Premiere)

Cthulhu Is My Fetish

Follow de’Lunula on the Tweet Machine and the Book of Faces.