Watch out, the world’s behind you

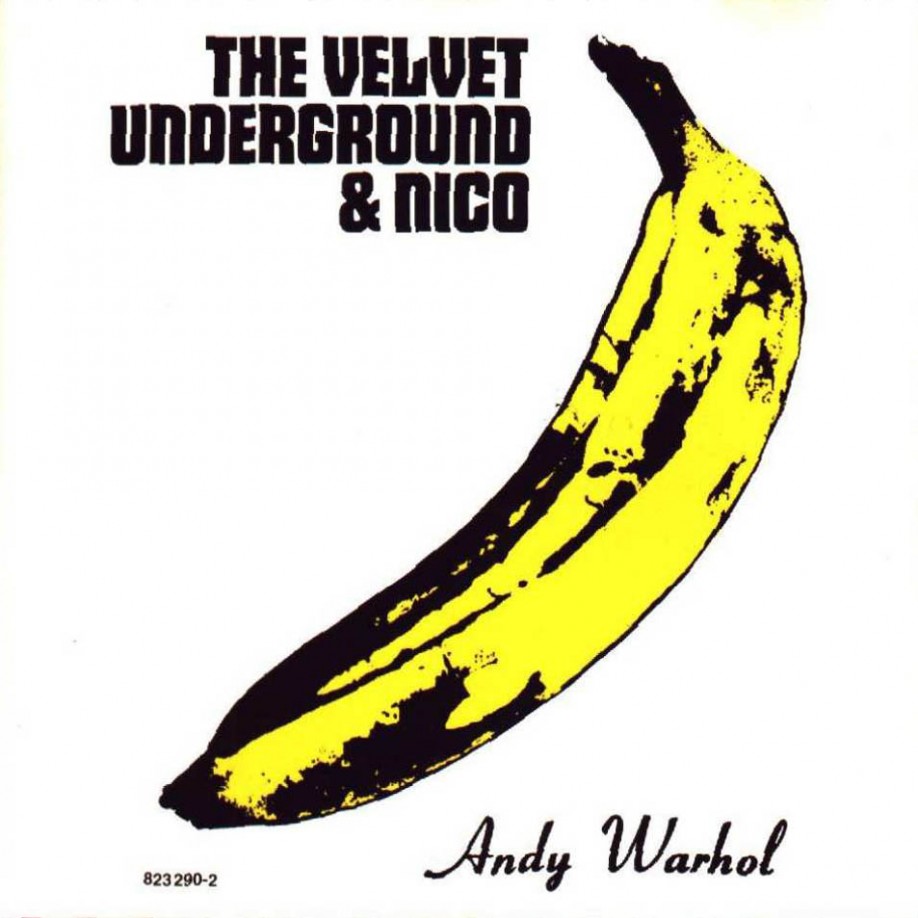

The Velvet Underground & Nico turned 50 a few days ago. Half a century has passed since The Evil Beatles left their track mark on the world. 50 years… that’s a lot of peeled banana stickers. Five decades worth of bands biting their black-clad, too-cool-for-anything style & critics recycling that Brian Eno line about them only selling 10,000 records but every single person who bought one started a band. Fifty years worth of ink spilled about how that first album was the underground’s Yggdrasil, the world tree from which punk, glam, noise, goth, krautrock, and god knows how many other subcultures would bloom into being on its many branches.

If The Beatles were at the forefront of a British Invasion, the Velvets were the secret chiefs of an American Insurrection. The heroin-laced spearhead of a musical movement that was loud, snide, drenched in feedback, and more interested in telling you to go fuck yourself than hold your hand. And the banana album, that stark white object of Warhol branding, was that insurrection’s Declaration of Who Gives A Fuck. A statement of intent that still packs a wallop, half a century later, because it sounds like it’s not really trying in the first place.

First thing you learn is that you always gotta wait

The Velvet Underground & Nico is one of my favorite albums. It was a gateway drug for me, exposing me to glam, punk, and goth music. I started painting my fingernails black (which I do to this day) because Lou painted his black, too. Listening to the S&M imagery in “Venus in Furs” filled me with a sense of… curiosity, and recognition. Like I was learning about something I always knew I liked but didn’t have the words to describe.

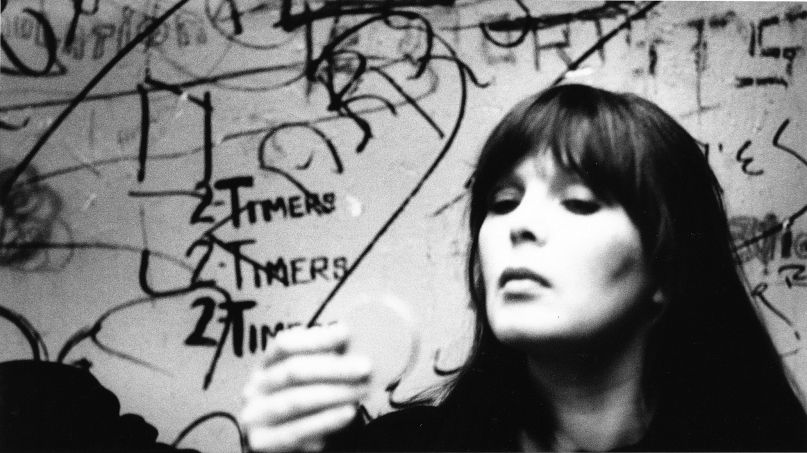

The lyrics were smart and poetic but weren’t afraid to be on-the-nose when they had to be. The music was chaotic and unpredictable, veering from lovely pop to cacophonous squalls of strangled guitar strings and epileptic viola noises. Lou and Nico’s voices were emotional flatliners; they undersold the songs, singing with half the emotion you’d expect them to have and letting the music (and you, the listener) fill the rest of it in. Sometimes they even seemed to be mocking the music itself- the half-hearted backing vocals in “Femme Fatale” and “There She Goes Again” sound like the band, weened on doo-wop and classic rock, doing a piss-take on the music of their youth. And through the whole thing, there was Moe Tucker’s drumming, a faint mother’s heartbeat, the wobbly and insistent anchor holding everything together.

Listening to the album over the last week, what struck me most about it is how I can still hear new things in it. It’s the hallmark to any great piece of art: it keeps revealing new aspects to itself as your relationship to it deepens. The best movies, music, books, and paintings have an inexhaustible supply of secrets. They’ll keep sharing them with you if you’ve got the patience to stick around and listen.

She’s gonna play you for a fool, yes it’s true

One thing that leapt out, listening to this record I’ve heard about a hundred times before, was I never paid much attention to the quality of the production before. It’s interesting to contrast their first record with their later efforts. The production on White Light/White Heat makes it sounds fuzzy and crackling, like the whole thing is being piped through flaming speakers. The self-titled third record is hushed and clear sounding- it sounds like the whole thing was recorded in a pristine, soundproofed closet. And then there’s the polished recording of Loaded, their most radio friendly album (and their least interesting, in that it’s the one Velvet Underground album that sounds like it could have been made by someone else).

The first album stands out as being a little of all the above. Tom Wilson and John Cale’s production work captures the pop appeal of the band (esp. in the Nico numbers), but let enough static, feedback, and dirt into the sound that it gives the album a weird, almost live-recording atmosphere. Listening to The Velvet Underground & Nico today, the album sounds like messed-up taped radio sessions. The band jamming live on the air, or in the hermetically sealed environment of a late night talk show.

The Nico songs sound more like studio numbers. The music for “Femme Fatale” and “I’ll Be Your Mirror” is more delicate and crystalline. It wouldn’t be hard to imagine them being redone as Motown tunes. And while Nico’s funeral torch singer schtick is cool and reserved, it’s the emotional center of the record. No matter how turbulent or fevered his lyrics get, there’s a distance in Lou’s voice. Even if he’s singing about something that happened to him directly, he intones it in a way that makes you think he’s talking about someone else.

Her three spotlights on the album burn so bright because it feels like the band at their most naked and exposed. No matter how much they resented the inclusion of Nico on the album, the Velvets were just like most of their 70’s New York punk children: they wanted success. While the rest of their album may have been them thumbing their nose at pop concessions, making avant-garde moves and flexing their drug-filled muscles, it’s those quieter numbers with Nico where you can feel them trying to plant their banana flag next to The Marvelettes.

I could sleep for a thousand years

When I think about the first VU record, I often think of Stop Making Sense. I think of the structure of the film- how the Talking Heads concert starts with just David Byrne onstage. On each subsequent tune, he’s joined by more members of the band until the entire expanded lineup of the Heads is jamming onstage. It’s a neat bit of pacing and storytelling, showing the evolution of the band’s sound and personal history while also building anticipation in the viewer & audience for them to get to their “big” numbers (the thrill of seeing all the Heads and their new recruits onstage is knowing that they’re now able to play songs off Remain in Light & Speaking in Tongues). I think about this film when I listen to the VU because it seems like their career is Stop Making Sense played in reverse.

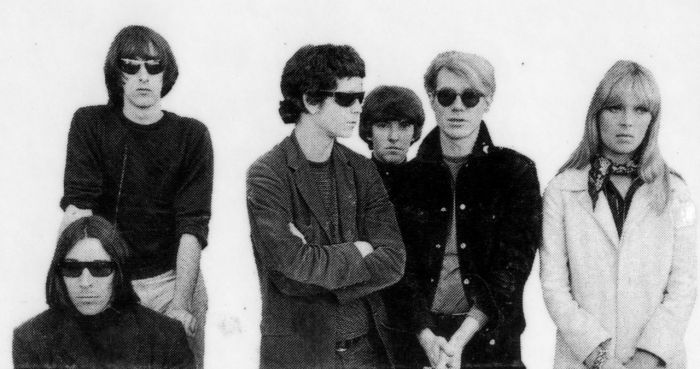

On that first album, the Velvets are as big and busy, musically speaking, as they’ll ever be. It has Reed & Sterling Morrison on it (the only two original Velvets to appear on all four of their studio albums), Moe Tucker, John Cale, and Nico. After the first album dropped, the band also dropped Nico. Perhaps too soon: it’s hard to imagine Lou didn’t kick himself when he realized that Nico not singing “She’s made out of wood” on “Here She Comes Now” was a huge, passive-aggressive missed opportunity.

They not only lost a second singer, they also began to shed their Warhol connections and delirious live show. After the second album, they lost Cale. Cale’s viola was a key aspect of the band’s sound, giving them something dissonant and unnerving that no other band had in their mix. With him gone, the band severed their ties to the musical avant-garde that Cale had deep roots in. In some ways, it makes perfect sense: how do you make music that goes further than “Sister Ray”?

And then, after their intimate third album, they lost Moe Tucker. They also picked up Doug Yule during this process of shedding band members, but his presence and influence on the band is a story for another time. What makes this process of slimming down fascinating is that most bands work in the opposite direction- they start small and expand over time, adding more members and experimenting with the boundaries of their sound. The Velvets started with their largest ensemble, with the most expansive palette of sounds to play with, and over the course of four albums stripped themselves down to their bare bones. They started as Remain In Light and ended as David Bryne, alone onstage.

But I’m gonna try for the kingdom, if I can

Every song on the first VU album sounds like it could have inspired its own musical subgenre. You can hear the seeds of chamber pop, shoegaze, alternative rock, noise, punk, post-punk, even twee (try to imagine Beat Happening without Moe Tucker’s example) in the grooves of the album. And while the album has been ruthlessly mined for inspiration, there are still moments on there that nobody has been able to do better. Bolts of lightning that refuse, 50 years later, to be bottled up.

“Heroin” is one such bolt. Perhaps the greatest song about drugs ever recorded. The way that the lyrics and the flow of the music perfectly match each other. How the tune sinks into idle, slow reverie as Lou talks about being caught in the grips of opiated bliss. How the beat (sounding like a shriveled, overworked heart) desperately starts pounding and the violas saw frantically to meet the quickening pace of Lou’s words, as he is rattled by the drug rush. The push-pull between consummation and desire, copping and withdrawing, wanting to quit versus not giving a shit about dying. It’s a perfectly ambivalent song- you can HEAR why Lou loves the drug, just as you can hear the horror it provokes in him too. And the way the song trails off after it comes down from a final spike of noise, leaving you without any answer- “oh, and I guess I just don’t know”…. all these years later, it’s still hard for me to think of another song with a more quietly devastating ending.

Your clown’s bid you goodbye

Speaking of endings: how perfect is “European Son”? It starts as a simple vamp of a number, one more nervy and tense guitar showcase. And then comes THE SOUND- Reed and the band in studio shatter a glass while dragging a chair across the floor. The sound of that breaking glass, followed by the tremendously loud scraping sound (like a train hitting the brakes a second too late, plowing right into a wall of tin) is the song’s starter pistol- it kicks the guitars into overdrive, a final mini-freakout before they clock out of The Factory for the night.

Divorced from its history, it’s a record that still sounds vital. It’s beautiful and ugly. It begs for your attention and then swats at you when you get too close to it. I hope that when I turn 50, I’ll look and sound as good as The Velvet Underground & Nico does in 2017.

Ashley Naftule is a writer, performer, and lifelong resident of Phoenix, AZ. He regularly performs at Space 55, The Firehouse Gallery, Lawn Gnome Books, and The Trunk Space He also does chalk art, collages, and massacres Billy Idol songs at karaoke. He won 3rd place at FilmBar’s Air Sex Championship in 2013. You can see more of his work at ashleynaftule.com

Watch the Premiere of “ORANGES,” a horror film about fruit.

We Gave Travis James Bath Salts For Some Reason

Announcing PHX SUX, Our ‘Fuck You I Love You Phoenix’ Art Show, Plus de’Lunula Screeners #4!

Follow de’Lunula on the Tweet Machine and the Book of Faces.