“Belladonna of Sadness” Is A Film Worth Selling Your Soul For

by Ashley Naftule on Mar 8, 2017 • 12:57 pm 55 Comments

“Only darkness has the power.” -The Mekons

Towards the end of “Belladonna of Sadness”, Eiichi Yamamoto’s gorgeous & hallucinatory 1973 animated masterpiece, an orgy breaks out in the woods. Presided over by a witch, villagers cavort and comingle in the forest. They give in to their animal urges, turning into beasts in the process. A man’s penis appears as a giraffe’s neck jutting out from his lap; a woodpecker lands and pecks away at one reclining woman’s vagina, while fish fly out of another woman’s. Survivors of the Black Death that decimated their village, the peasants dissolve their minds and bodies in a feverish sex party that looks like it was conceived by Ralph Bakshi on DMT.

“Belladonna of Sadness” is a film that’s obsessed with sex, but not necessarily in the way that you’d think. It isn’t like the hentai films it’s inspired over the years; it doesn’t linger on the explicit details. The animation style is fluid and rapid; during the aforementioned orgy scene, so many strange visuals flash by the screen before you have a chance to really register what you’ve seen. Trying to keep up with its wild blur of imagery is a lot like trying to appreciate every joke in a Marx Brothers movie during your first viewing- it comes at you too fast to catch it all.

The story of “Belladonna” is fairly straightforward. A married French couple, Jean and Jeanne, get summoned to the castle of their lord. Invoking Prima Nocta, the ghoulish lord rapes Jeanne on their wedding night in a disturbing, nightmarish sequence: black, leering demons hold her down while the lord literally splits her body open, the act of rape depicted as a throbbing red spike pulsing in and out of the whole of her being. The couple return to their hut. A humiliated and angry Jean withdraws from Jeanne. Eager for power, she’s approached by the Devil, who offers to give her what she wants in exchange for her body and soul. She refuses him… but not for too long.

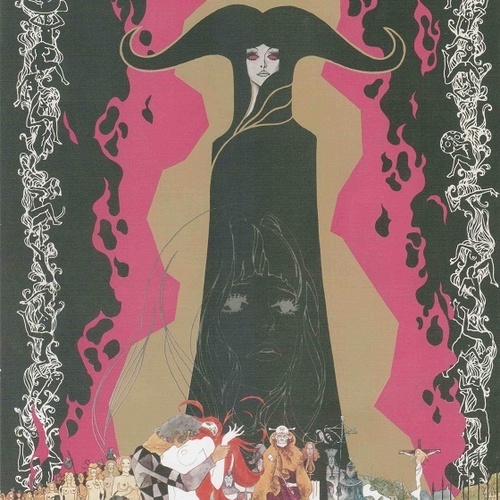

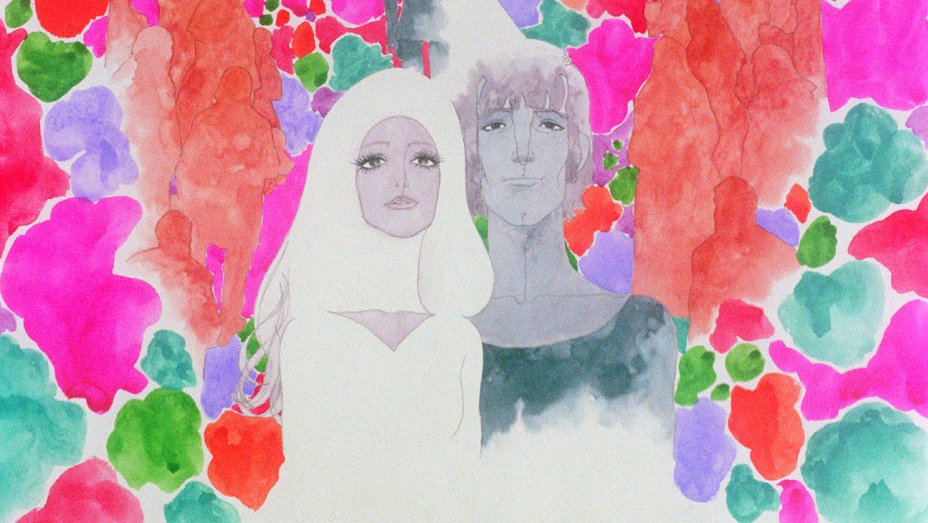

One of the first things that stands out in “Belladonna” is its unique animation style (a style whose closest relatives are the works of Bakshi, Rene Laloux, and Heavy Metal). The first few minutes of the film are rendered in still frames, with the camera zooming in and panning around large scrolls of intricate and colorful artwork. The art style looks like a psychedelic hybrid of Gustave Klimt and Alphonse Mucha’s work. Watching “Belladonna”, you can see the long shadow it must cast over Japanese animation as a whole, as well as on the work of artists like Yoshitaka Amano and David Mack.

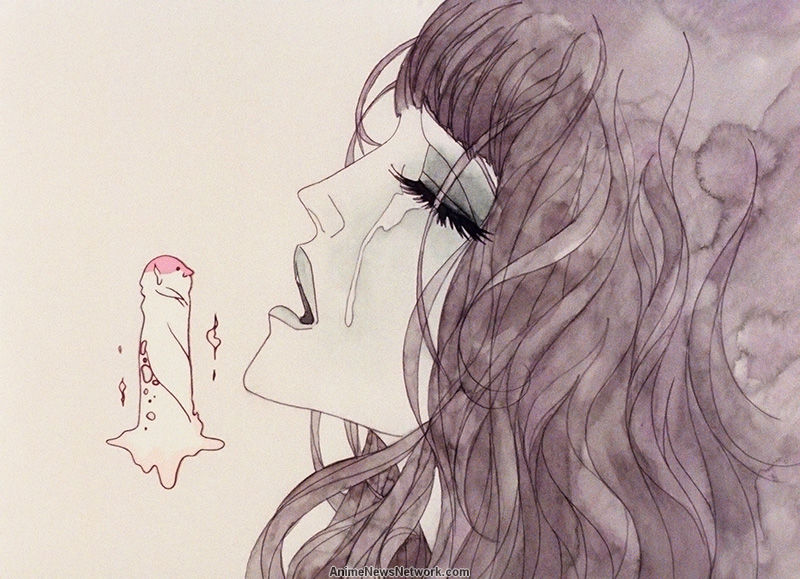

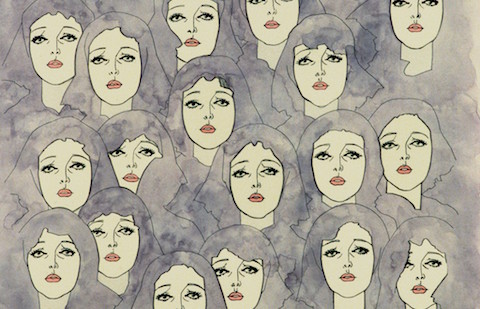

The animation doesn’t stay static for long: the images start coming alive, but Yamamoto doles out movement sparingly. For viewers used to watching animated films where everything is in motion, the relative stillness of “Belladonna of Sadness” can be shocking. That stillness is something the film use masterfully; it makes the more hallucinatory passages in the film even more disorienting because they surge and pulse with an urgency that the rest of the film is denied. Yamamoto also employs negative space to great effect, using the white backdrop of his frames to create a sense of vastness in his images (which are often half-completed, looking like they’re dissolving into their backgrounds).

While the images often sit still, the music rarely does. “Belladonna” is propelled forward by a soundtrack that is, quite frankly, batshit insane. It shifts gears constantly, veering from ominous tones to bucolic folk, cheery Japanese pop to spastic acid rock, psych-rock freakouts to Herbie Hancock style jazz. So even when nothing is moving within the frame, the music gives you the impression that the entire world is about to collapse at any moment.

As the film progresses, we watch as Jeanne and the Devil evolve. The Devil first manifests as a phallic-shaped Freudian sprite, barely taller than a pinkie. As it exerts greater influence on Jeanne, it grows in stature, manifesting as vines, butterflies, blooming flowers, and a towering devil (all of which still look like dickheads). Jeanne herself changes over time, adopting a Maleficent style high collar green robe and bewitching the villagers to her side. Cast naked into exile by the lord’s jealous wife, she finally submits to the Devil. And that’s when the film takes a very unexpected turn.

Jeanne’s life, up until the moment she submits to the Devil, is basically terrible. Raped by lords and demons, ignored and occasionally abused by her drunken husband, hated and envied by other mortals, she tries to make the best of her situation. She refuses the Devil’s offer of power… but as soon as she accepts it, her life improves dramatically. Taking the Devil’s power gives her agency, strength, cunning, and secret knowledge. In most media, pledging allegiance to Satan would be seen as a terrible decision; for Jeanne, selling her soul is her salvation. It feels like she wasn’t resisting the Devil this whole time, but rather her own desire to take control of her life. If that reading sounds like a stretch, consider this: the Devil never comes back after “the deal” is made.

When Jeanne sells herself, the film explodes into its most deranged section. It becomes completely unmoored from its own time period, jumping throughout history. We see school buses, jutting skyscrapers, dancing hippies, Afros, and hundreds of other lightning fast images that are done in a style that can best be described as “Schoolhouse Rock on bad acid’.

In some ways, it’s reminiscent of what happens towards the end of Bunuel’s “Simon Of The Desert”. Saint Simon, standing on his pillar in the desert, is finally overcome by Satan. Satan whisks him away from his medieval life on an airplane, taking him to the 20th century where the once-ascetic holy man is now a cynical hipster, sharing cocktails with the Devil while they watch hip kids freak out to rock & roll on the dancefloor. It’s almost as if Jeanne and Simon have become unplugged from the Matrix: by giving in to the temptations of the Devil, they’re freed not just from the tyranny of conventional behavior and morality, but from time itself.

After “crossing over”, even sex itself takes on a different dimension in Jeanne’s world. Before, sex was something that happened TO Jeanne, something that she had to endure. Now, empowered as a witchy woman, she instigates it and presides over it. Sex goes from something that’s a nightmare to a dream, an oceanic experience that tangles up and merges its participants, dissolves their boundaries and realities, unifies them. It goes from a Prima Nocta dictatorship to a democratic activity, something that everyone does with everyone else. Once a tool used to put women in “their place”, now it’s something that threatens the lord’s power. Which leads to the film’s bloody (yet oddly truimphant) climax. Executed by the lord for witchcraft, Jeanne’s spirit possesses the womenfolk of the village, inspiring the women of France to lead the charge against the Bastille years later.

The ending underlines just how subversive a movie “Belladonna of Sadness” is. This is a movie where darkness has the power. A woman sells herself to the Devil and not only does it lead to her liberation and self-actualization, it brings about a revolution that liberates everyone else! It’s no coincidence that the only representative of God in the story is the shifty priest who serves at the rapacious lord’s right hand. Yamamoto’s film takes that famous line from “Spaceballs” and tweaks it: “Evil will always triumph because Good is wrong.” And when “evil” gets you an invitation to a forest orgy where your genitals can turn into zoo animals, who in their right mind would say no?

If you haven’t seen this masterpiece of psychedelic animation yet, you’re in luck: the film is still in print and available via stream or Blu-Ray.

Ashley Naftule is a writer, performer, and lifelong resident of Phoenix, AZ. He regularly performs at Space 55, The Firehouse Gallery, Lawn Gnome Books, and The Trunk Space He also does chalk art, collages, and massacres Billy Idol songs at karaoke. He won 3rd place at FilmBar’s Air Sex Championship in 2013. You can see more of his work at ashleynaftule.com

The ‘Angel Bay Files’ is the Only Detective Show with Fish Actors

We Gave Travis James Bath Salts For Some Reason

Fathers Day – ‘Disney World’ (Music Video Premiere)

Follow de’Lunula on the Tweet Machine and the Book of Faces.