“Dead, dead, dead, dead, dead, he’s fucking dead, the guy from Brainiac is fucking dead. I want this to mean something to every fucking one of you.”

Those were the first words that Jeff Buckley said when he went onstage at Barristers. A little hole in the wall bar in Memphis, Buckley played a show there on Monday, May 26th, 1997. Three days later, Buckley took a dip in the Mississippi River and swam out of this world. The gig at Barristers was his final live performance, an evening he dedicated to the memory of Brainiac’s lead singer. Tim Taylor had died on Friday the 23rd of that month when he lost control of his Mercedes and it collided with two poles and a fire hydrant. He was just a year shy of turning 30, the age Buckley was when he dove into the Mississippi.

Looking back on it, it’s an eerie moment in musical history. One musical legend, just a few days away from his own tragic death, bleeding his heart out onstage for another member of the Gone Too Soon Club. Buckley dedicated “Hallelujah” to Taylor’s memory; towards the end of his set, he dusted off “Corpus Christi Carol,” a song he hadn’t played live in years. “Is that how you like your rock heroes – dead?“, the son of a dead rock hero asked his audience.

Considering the timing of the two deaths, it makes me wonder if Buckley didn’t have some kind of twinge of premonition. Perhaps he saw himself, burning to death in the front seat of Taylor’s crushed Mercedes. And maybe Taylor had a similar feeling as he drove towards his Dayton home. For all we know, Taylor could have been humming Buckley’s “Last Goodbye” as his car careened off the road, a final vision of night-swimming flashing before his eyes at the moment of impact. Two artists who couldn’t have been more different, briefly united by a web of unfortunate coincidences.

The big difference between them is that there’s a good chance you haven’t heard of Taylor. Buckley’s early death catapulted him to posthumous immortality. His legendary status isn’t undeserved: while Grace isn’t a stone-cold classic from front to back, it is a record full of enough indelible moments and stunning vocal turns to make his absence in the world deeply felt. Listening to Grace is like listening to the ghosts of a dozen records that will never be. You can’t help but wonder what the future had in store for Jeff. Perhaps he would have released a string of brilliant albums and then retired from the industry. Maybe he would have gone pop; eventually, he’d end up being a judge on American Idol, smiling politely while pop star hopefuls thirsty for a Max Martin cosign butchered “Lover, You Should’ve Come Over”. When Leonard Cohen died, he’d sing “Hallelujah” at his funeral, barely holding himself together. Some nights he’d wake up in a cold sweat, dimly recalling dreams of thrashing beneath the skin of a dark river and wonder what it meant.

Buckley’s death enshrined him in the Hall of Musical Heroes. Any documentary on 90’s music will mention him. His face will still grace magazine covers for retrospectives. His death is a generational “where were you when you heard” moment. Tim Taylor wasn’t so lucky. Brainiac was still too much of a fringe act for his death to take on a mythic quality. He didn’t get to die The Death Of A Dream; his grave wouldn’t get papered over with magazine covers and headshots from actors hoping to play him one day.

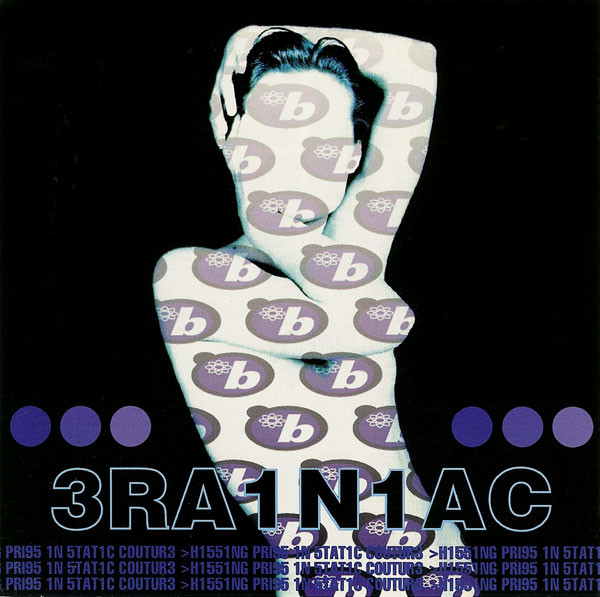

His death should be considered in a similar light to Buckley’s, though, because it’s impossible to listen to Brainiac’s albums and not think about what they could have become. By the time of Tim’s passing, the Dayton band had already released three studio albums: their jittery Devo-meets-caffeinated punk debut (Smack Bunny Baby); one extraordinarily assured sophomore album (Bonsai Superstar, which was the band’s first album with guitarist/future Enon frontman John Schmersal); and a straight-up masterpiece (Hissing Prigs in Static Couture). They also put out a pair of EPs: Internationale, their 1995 Touch & Go Records debut (produced by Kim Deal); and the Jim O’Rourke-produced Electro-shock For President, released just a month before Taylor’s death.

Electro-shock for President turns 20 this Saturday. The experience of listening to that EP is a lot like listening to Grace: it’s impossible not to wonder about what could have been. The band released the EP as a teaser for their fourth studio album; they had just begun pre-production on the album when Taylor passed away. The six song teaser was meant to show off the band’s new musical direction, hinting at a bold new approach they’d never get a chance to master.

The band abandoned guitars entirely on the new EP, relying on electronics and Tyler Trent’s forceful drumming. Electronics had always been an integral part of Brainiac’s sound. They took the synthetic mad scientist sounds that groups like Devo and the Silver Apples had pioneered and married those bleeps and bloops to a chaotic rock and roll sound. Listening to Brainiac was like listening to the robot butler in a Shag painting go berserk. It was Space Age Bachelor Pad Music for speed freaks — psycho-nerd rock that was the sum of adding Juan Garcia Esquivel, Iggy Pop, and Mark Mothersbaugh together.

The rhythm section of Juna Monasterio (aka Monostereo) and Trent could effortlessly shift from funky James Brown breakdowns to spastic beat freakouts. The guitar playing of Schmersal (replacing founding guitarist Michelle Bodine after the release of Smack Bunny Baby) was as unpredictable and erratic as a Raymond Scott score: it wouldn’t be hard to imagine Schmersal’s crunchy yet fleet guitars soundtracking a fast-paced Duck Dodgers adventure, or slowing down into a sinewy groove so a cross-dressing Bugs Bunny could put one over on Elmer Fudd. Combine all that with the overdriven electronics that would sputter and wheeze and shoot off sparks all over their songs and you had a sound that was both retro and futuristic. A sound that groups like Polysics and Schmersal’s own Enon (for their early stuff, at least) would continue to explore after Brainiac’s dissolution.

While the contributions of Trent, Schmersal, Monostereo, and Bodine shouldn’t be underestimated, the most important facet of the band’s sound was Taylor’s voice. It’s probably the reason why he was on Buckley’s radar in the first place. Buckley was well-known for admiring singers who pushed at their boundaries and stretched their voices in strange new directions. Buckley’s favorite singers included vocalists as diverse as the Cocteau Twins’ Elizabeth Fraser, Qawwali singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, and Don Van Vliet (aka Captain Beefheart). All of them were singers whose voices soared to heavenly heights or burrowed deep into unfathomable underworlds. Of course, Buckley would be an admirer of a man who could shapeshift his voice as wildly as Taylor did.

In the early 90’s, Jim Carrey manipulated his face and body like he was the Elastic Man on cocaine. Taylor was his musical twin, a man who bent and twisted and rewired his voice. In a single song, the singer could hopscotch from garage rock hollering to robotic squealing to leering come-ons. He was so adept at shifting his voice (turning on a dime from high-pitched, almost-campy falsettos to flat mumbling on the mic) that it was hard to tell which vocals were processed/distorted and which were au naturel.

Not only were Taylor’s malfunctioning-party-robot vocals an outlier in 90’s rock culture, his persona was something we hadn’t seen before. For a band with such openly nerdy influences and interests, Brainiac were aggressive. They had swagger and an unhinged confidence in themselves, something that no other Devo-loving group had pulled off before. Taylor was a rabid spazz on the mic, and also a bit of a looney lothario. Any other band singing a song called “Sexual Frustration” would make themselves the victim of it; Taylor’s low, leering verses make it sound like he’s the cause of that frustration.

While Taylor was a master of the manic, flailing vocal take, he could also do creepy and insinuating. That side of him gets to shine on Electro-shock for President, as he whispers and hollers on the slow, pulsing “Fresh New Eyes.” The band turns the static dial up to 11 throughout the EP, creating an atmosphere that crackles with menace. Even when the band taps back into their epileptic might on “Mr. Fingers”, it feels more restrained than on past releases. But not restrained in the sense that the band had lost their touch or were watering their sound down- they sounded more like a coiled serpent, waiting for the right time to strike.

The glitchy, crawling electronics on Electro-shock for President hinted at a more sinister turn for the band’s sound. While earlier records seemed to depict a struggle between man and machine, human elements (Taylor’s vocals, the guitars) locked in a tug of war with synths and gear, this new EP was the sound of a band going transhumanist. They had become cyborgs, at one with their machines. Electro-shock for President was a herald for Brainiac’s merging with the Singularity.

Brainiac had beat Radiohead to the “Fuck Guitars” punch by three years. They blazed a trial that bands like Liars would follow years later, foregoing thunderous post-punk music for cold-blooded electronics. Who knows how far they would have taken it, or where Taylor and his gang of robot-loving cohorts would have gone next. All we have as a clue is Taylor’s defiant voice shouting “Dress my tongue in a new disguise/Go on and give me a sexy mouth to taste it” over a bed of synthetic noises that churned and writhed like cicadas erupting from beneath the soil.

Maybe those lines from “Fresh New Eyes” were on Buckley’s mind the last time he sang “Last Goodbye.” “Please kiss me/But kiss me out of desire, babe, and not consolation,” Buckley sang while his halo was being hammered out in rock and roll heaven. He got the kiss of desire from history; Taylor got the consolation. On 1996’s Hissing Prigs in Static Couture, Taylor squealed “Kiss me, you jacked-up jerk”. History wasn’t listening. Maybe he should have asked, “Is that how you like your rock heroes -dead?” instead.

Ashley Naftule is a writer, performer, and lifelong resident of Phoenix, AZ. He regularly performs at Space 55, The Firehouse Gallery, Lawn Gnome Books, and The Trunk Space He also does chalk art, collages, and massacres Billy Idol songs at karaoke. He won 3rd place at FilmBar’s Air Sex Championship in 2013. You can see more of his work at ashleynaftule.com

The Philae Comet Landing Was An Inside Job!!!

Donald P. Lovecraft, Or, The Doom That Came To Manhattan

Watch ‘The Back Road,’ An Apocalyptic Doc about Dean Chetwynd’s Dark Art

Follow de’Lunula on the Tweet Machine and the Book of Faces.