“Lincoln in the Bardo” Is A Scenic Death Trip

by Ashley Naftule on Mar 29, 2017 • 9:25 am 47 Comments

“Trap. Horrible trap. At one’s birth it is sprung. Some last day must arrive. When you will need to get out of this body. Bad enough. Then we bring a baby here. The terms of the trap are compounded. That baby also must depart. All pleasures should be tainted by that knowledge. But hopeful dear us, we forget.”

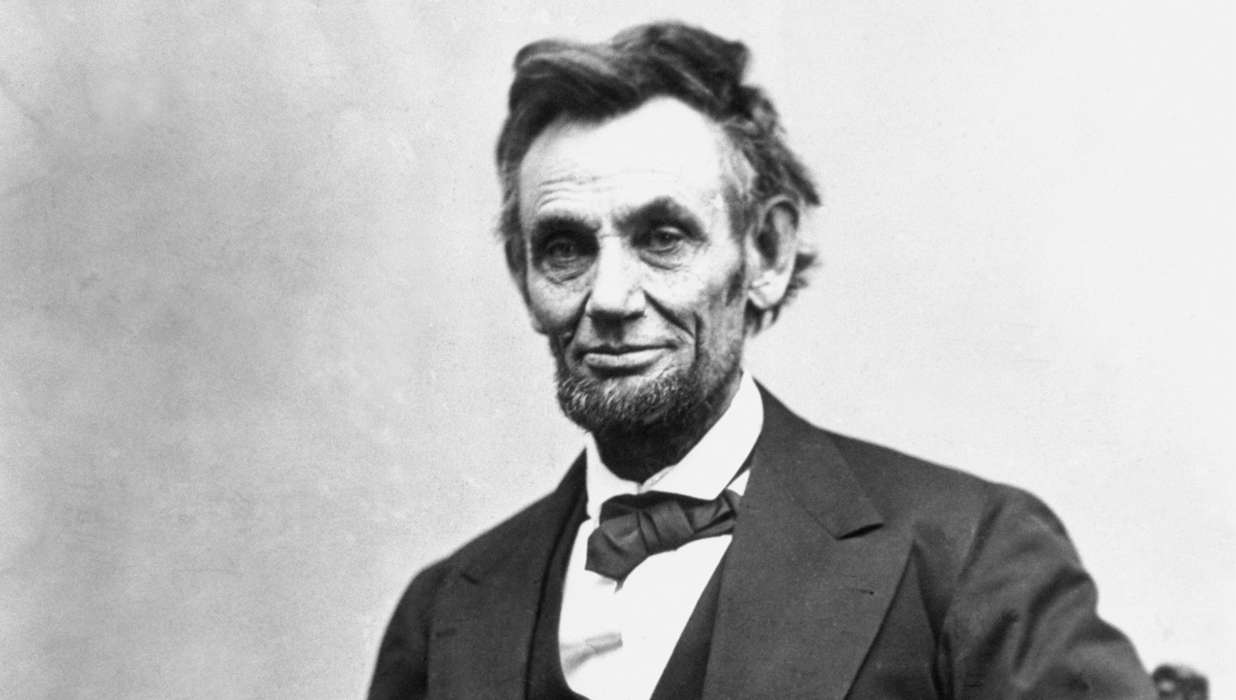

These are the thoughts that run through Abraham Lincoln’s mind as he hangs around in the cemetery that houses his beloved son Willie. The grieving President is just three years away from joining his son in the next world. Alone in the dead of night, the great man feels broken by his grief. But he isn’t alone- the spirits of the dead are watching him. And some of them are doing a lot more than just watching.

George Saunders’ “Lincoln in the Bardo” is a beautiful, lyrical, and haunting book. It’s also an infuriating one — his writing is so well-crafted and precise that I had to put the book down on several occasions and walk away before I succumbed to seething jealousy and hurled it out my window.

The structure of the book is composed like an oral history unfolding in real time. Everything in the book is either a direct quote from one of the (many, many) characters or an excerpt from a historical text about the time period it’s set in. Set in a liminal dimension between life and the great beyond, it focuses on a community of spirits trapped in the cemetery where Willie Lincoln is laid to rest. In denial about their present state (the spirits call their coffins “sick-boxes” and are convinced they’ll be back to normal any day now), they live a twilight existence where they endlessly retell their woeful life stories. Their spiritual bodies are malformed and sculpted by what afflicted them in life: some hover flat over the ground, while others boast gigantic flaccid penises or keep growing new limbs and noses all over their body.

Not since Koushun Takami’s “Battle Royale” have I read a novel that was able to expertly present such a huge cast of characters and make them all distinct. Takami’s book is often praised for its blood-splattered concept; it doesn’t get the credit it’s due for the economy of its storytelling. Koushun Takami can introduce and kill off a character in a single page and make them memorable. He gives us just enough details about their life and personality to make their death meaningful.

Saunders is able to pull off similar miracles of brevity in “Bardo.” Introducing us to a large group of spirits, he’s able to differentiate each of them with unique patterns of speech, vivid backstories, and freakishly strange ghost bodies. Some spirits only get one or two quotes before they vanish from the narrative, but they still make an impression. Considering Saunders’ gifts as a short-story writer, it’s no surprise he’s able to do such impressive character work in miniature.

What also stands out about “Bardo” is how fresh its vision of the afterlife is. The way the ghost bodies change and shift and blur into each other made me think of old super-imposed ghost photography, and the trick films of Georges Melies. Peter Pan-like spirits fly in the sky and rain hats down on the head, while carapaces of tiny moaning faces swarm over and entrap unlucky child spirits. The surrealistic bardo these Civil War spirits dwell in has its own internal logic and pecking order that Saunders reveals in drips and drabs of exposition, but leaves enough mysteries unanswered that I’m still thinking about that underworld, weeks after finishing the book.

The thing that haunts me the most about “Lincoln in the Bardo” is how timely it feels. There are so many echoes of the era we live in now in Saunders’ depiction of an America torn apart by in-fighting and spite. Reading period columnists and politicans write angry invective about the Lincolns throwing elaborate dinner parties while the republic burned, it wasn’t hard to think about conservative pundits going ballistic over Obama family vacations.

It also offers a sobering insight into how unreliable we all are, both as observers of history and as narrators of our own personal stories. Saunders stacks together passages of historical records that wildly contradict each other. Eyewitnesses to Lincoln’s grand party can vividly recall chocolate fish swimming in candy floss ponds and Chinese pagodas spun out of sugar, and yet none of them can agree on what the moon looked like outside. Or the colors of Lincoln’s eyes, for that matter. Reading so many different excerpts of “history” that can’t agree on something that should be as easy to deduce as the phase of the moon that’s hanging over their heads is deeply unnerving. How much of our knowledge of the past was shaped by people who saw a crescent moon in the sky and said it was full?

The ghosts themselves are just as unreliable. None of them can see or acknowledge the plainly self-evident truth that they are D-E-A-D. To be fair, though: the living aren’t much better off in the honesty department. After all, how much of our lives are dictated and hemmed in by people who can’t bear to face the truth?

In one of the book’s most haunting passages, the ghost of a slave who was treated “like he was part of the family” looks back on his life and realizes how much of it wasn’t his own. Looking back on his old life, where he would get a few breaks a week from his labor, he realized how much he gave up to believe the lie that his masters were good people:

“And yet, still: I had my moments. My free, uninterrupted, discretionary moments. Strange, though: it is the memory of those moments that bothers me most. The thought, specifically, that other men enjoyed whole lifetimes comprised of such moments.”

Ah, the bitterness of tasting freedom: knowing that somewhere there’s an asshole who’s been drinking it up and pissing it away for years while you’ve been dying of thirst.

“Lincoln in the Bardo” is a moving, eerie meditation on self-delusion and death. It serves as a rousing reminder to chase after as many of those free, uninterrupted, discretionary moments as you can get. It’s also a brutally honest look at how painfully temporary our relationships are, how the ones we love most are no more permanent than a Tibetan sand mandala:

“Two passing temporarinesses developed feelings for one another. Two puffs of smoke became mutually fond.”

Hold your puffs of smoke close. There’s no telling when they’ll dissolve into the night sky.

Ashley Naftule is a writer, performer, and lifelong resident of Phoenix, AZ. He regularly performs at Space 55, The Firehouse Gallery, Lawn Gnome Books, and The Trunk Space He also does chalk art, collages, and massacres Billy Idol songs at karaoke. He won 3rd place at FilmBar’s Air Sex Championship in 2013. You can see more of his work at ashleynaftule.com

Announcing PHX SUX, Our ‘Fuck You I Love You Phoenix’ Art Show, Plus de’Lunula Screeners #4!

No Volcano — “New York Drugstore” (Video Premiere)

We Gave Travis James Bath Salts For Some Reason

Follow de’Lunula on the Tweet Machine and the Book of Faces.