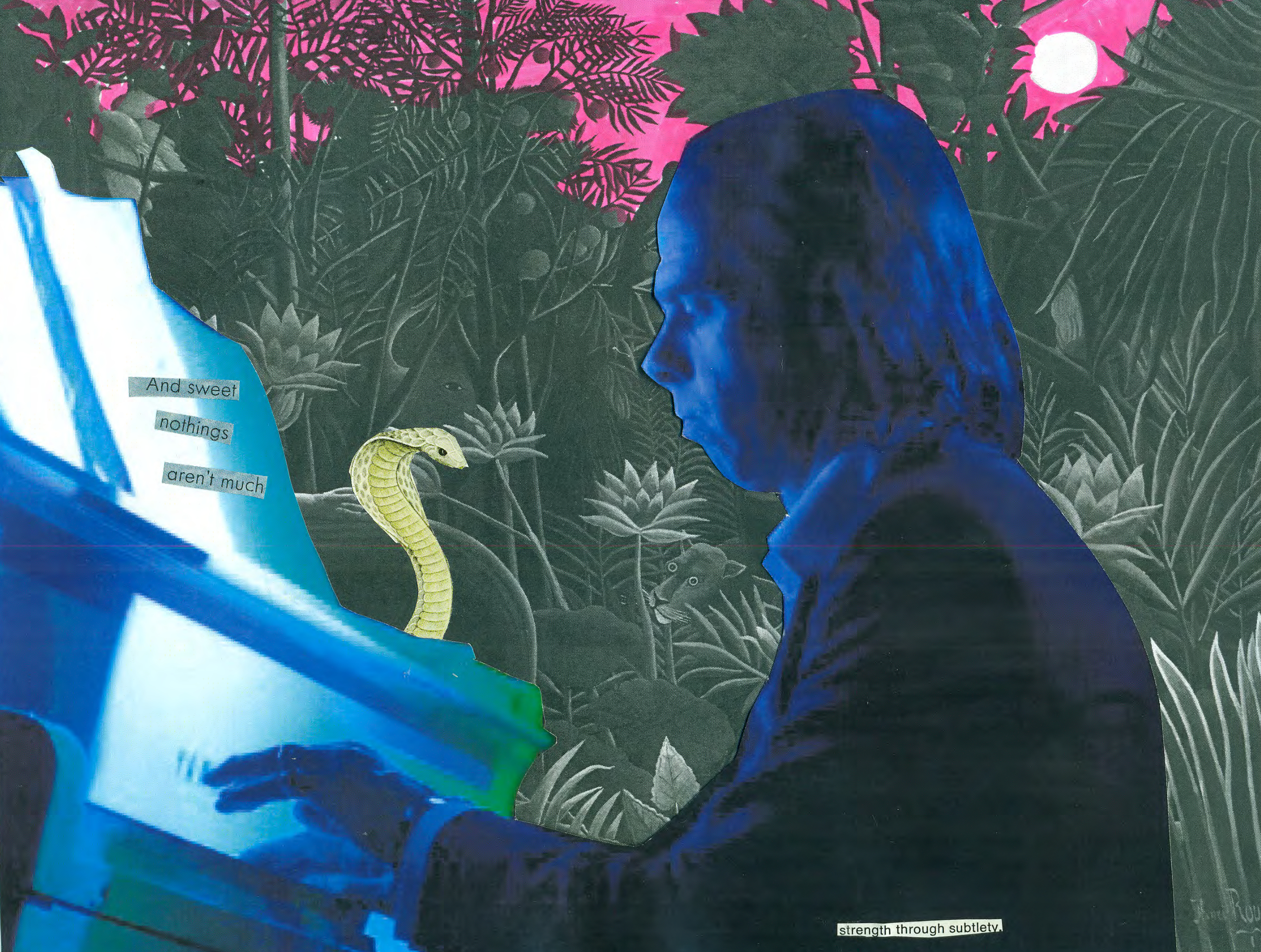

Collage by Ashley Naftule

“They told us our gods would outlive us/But they lied.”

-Nick Cave, “Distant Sky”

Nick Cave is a “battered monument.” It’s what director Andrew Dominik called him once, as a compliment, Cave tells us on camera in Dominik’s “One More Time With Feeling”. His unease about being anyone’s monument is plainly etched on his face. He frets about the bags under his eyes. Dominik talks about our bodies decaying with age from behind the camera; Cave, in front of the camera, admits to feeling diminished with the passing of time. He confesses that it takes more and more effort to keep doing what he’s always done. Seeing this, hearing this, from a living legend- It’s like watching the Sphinx mourn her missing nose.

“One More Time With Feeling” is a beautiful movie, and a haunting one. It follows Cave and his Bad Seeds as they put the finishing touches on their most recent album, “Skeleton Tree”. Dominik chronicles them at work in the studio, using a 3-D black and white camera that swoops and drifts around them like a spectral presence. There’s no attempt to mask the artifice of film-making: We see the lights and cameras at work, we see the dolly tracks that surround Cave’s piano. He lets us in on a secret that anyone who’s worked on a film set knows to be the absolute truth: Film-making is 80% waiting for shit to happen and 20% doing the same thing over and over again until it looks like you’re doing it for the first time. For all its glamour and prestige, making movies often amounts to a LOT of mind-numbing repetition and boredom.

If “One More Time With Feeling” was just about the making of “Skeleton Tree”, it would still be a compelling watch. Visually it feels like another link in the chain of art films like ‘Wings of Desire” or Chris Petit’s “Radio On”, with its slow camera movements and stark, gorgeous B&W imagery. It was hard not to keep thinking about ‘Wings of Desire” while watching it: Cave’s philosophical narration over the film made him sound like one of the weary angels in Wenders’ film.

But Dominik’s film is about much more than the making of an album: It’s about reckoning with a profound absence. Cave and his wife Susie Bick lost their teenage son Arthur while Cave started working on ‘Skeleton Tree”. His death haunts every frame of “One More Time With Feeling”. How the film deals with that loss is fascinating. In the film’s opening interview with Cave’s right-hand man Warren Ellis, he brings up the trauma and tragedy that surrounds them all without explaining it. And for most of the film, that’s how it’s treated: As this nameless tragedy that’s pressing down on everyone. Nobody puts a face or name to it: It’s too close to talk about it directly, too recent. We don’t actually hear Arthur’s name until the movie’s halfway over. And when Cave and Susie start opening up about his passing, they never refer to him as their son. Nor do they show us any pictures of him: We see paintings he made, we see his empty room, we see piles of what are probably his skateboards in their hallway, but we don’t see him. He’s gone, a ghost, a void that the film wisely doesn’t try to fill in.

In some ways, Dominik’s film harkens back to another B&W art house icon: Michelangelo Antonioni, whose slow moving, sumptuous films are obsessed with absences. Whether it’s the girl who goes missing (and is eventually forgotten) in “L’Avventura” or the main couple who vanishes in the last ten minutes of “L’eclisse” (which doesn’t stop the film from rolling on without them), his classic films are as much defined by the people we don’t see as the ones we do. It’s impossible to imagine “One More Time With Feeling” or the music on “Skeleton Tree” without Arthur Cave. He hangs over the work like the God that Cave evokes in his songs, the God that rests on the cross Ellis wears around his neck: A mute, inescapable omnipresence. Who knows if Arthur is as deaf to the music made in his memory as God is to our prayers?

“One More Time With Feeling” rarely hits any false notes. It feels authentic and truthful in a way that makes most other music documentaries feel like forgeries. The only time the film ever seems poised to go off the rails is towards the end, when it suddenly shifts from B&W to color for the performance of “Distant Sky.” At first the color change is exhilarating…. And then Dominik’s camera passes through the body of soprano singer Else Torp, sailing past networks of veins in her body, to drift out of the studio, out of Brighton, and out of the world to circle the Earth in space. For a moment it feels like the film’s been hijacked by Gaspar Noe.

For a film whose strength lies in feeling small and grounded and intimate, making such a grand cosmic gesture feels wrong. It feels like an undeserved, cathartic ending… but then the color switches back to B&W as we crash back down to Earth. The real ending, where we HEAR Arthur Cave for the first time, is still to come. The ending where it feels like the film reaches into your chest and rips your heart out so you can listen to it beat over the credits.

The first time we see our battered monument, he’s in a hotel room getting dressed for the camera, ruminating in voice-over about the elastic nature of time. He wants to believe in the idea that all things are happening at once- that a caveman is clubbing his mate at the exact same moment as a scientist figures out how we can get out to space- but he can’t. Yet the film that shadows his every move proves the theory right, as we see him work out music in real time while commenting in overdubs recorded from the future about his feelings about the past.

The film cuts from past, present, and future so many times that it feels like everything is happening at once, everything is piling on top of each other in the same way that Cave describes how his fractured narrative lyrics work. Life is random and chaotic and impossible to get a grip on, the battered monument tells us. The battered monument who’s written more songs, novels, and screenplays than most of us can hope to achieve in three lifetimes. If he can’t make sense out of any of this, what chance do the rest of us have? What hope is there for us mere mortals when even our gods have lost the plot?

Watch the Premiere of “ORANGES,” a horror film about fruit.

No Volcano — “New York Drugstore” (Video Premiere)

No Volcano – ‘The Long Game’ (Music Video Premiere)

Follow de’Lunula on the Tweet Machine and the Book of Faces.